Let’s talk about how we can build your commerce project — tailored to your business, powered by Mercur

If you run an eCommerce business, growth usually feels predictable at the beginning.

You add products, improve conversion, and increase ad spend. GMV goes up. The team grows. Each new channel looks like another lever you can pull.

Then, somewhere between 10-50$M in GMV, the pattern starts to change. This is a critical stage, and about 73% of brands fail to successfully move past it and scale to an enterprise level.

Not because your product suddenly got worse. Not because your marketing team forgot how to run campaigns. But because the economics of a “classic” eCommerce model change with scale:

- Your cheapest acquisition channels saturate, and CAC starts rising faster than revenue.

- Inventory becomes a bigger bet, tying up cash and increasing risk.

- Operations get more complex in ways that don’t show up in a neat dashboard.

- Growth becomes increasingly linear – every extra unit of GMV costs disproportionately more effort, capital, and coordination.

At that point, the question stops being “How do we grow faster?” and becomes “What needs to change in our model so growth doesn’t get more expensive every year?”

This article breaks down that moment. You’ll see why it happens, how to recognize it early, how marketplace vs eCommerce model compares, and how the best players respond once classic eCommerce stops being a growth engine.

Key takeaways

- The scaling wall is not defined by a GMV number, but by when growth starts getting more expensive with each step.

- The organizations that successfully scale past the $50 million ceiling are those that transition from being a "store" to becoming a "platform".

- Rising CAC, inventory pressure, and operational complexity are symptoms of a business model reaching its limits.

- The next phase of growth doesn’t come from pushing the same engine harder. It comes from changing how growth is generated in the first place.

- Marketplaces don’t replace eCommerce. They extend it by shifting risk, effort, and growth inputs outside the core business.

- Adding a marketplace layer doesn’t require replatforming. It can sit next to your existing stack, regardless of whether you run Shopify, Magento, or a custom setup.

- The strongest teams start narrow, prove the economics, and evolve the model over time instead of betting on a full transformation.

What “X million GMV” really means (and why it’s not the same number for everyone)

A classic eCommerce business often grows very fast at first, and then suddenly slows down. At some point, it hits a wall where growth becomes much harder. This is often called the “Scaling Wall.”

Research on DTC brands shows that this point usually appears between $10M and $50M in annual revenue. Below this level, companies usually grow efficiently. Founders are closely involved, decisions are fast, and brands can win by serving small or underserved niches.

Once a business passes $10M in GMV, those same early strategies often start to break down. Manual fulfillment, improvised marketing, and centralized decision-making no longer scale and begin to slow growth instead of supporting it.

The table below shows how growth efficiency changes as revenue increases and explains why the $10M–$50M range is where many eCommerce businesses hit the scaling wall.

For founders and leaders, the key question is: where is that breaking point? In other words, at what revenue or GMV level does the limits of a single-merchant, inventory-based model start to block further growth?

Here are the factors that decide where “X” shows up for you:

- Purchase frequency: If customers buy weekly, you can tolerate a higher CAC and still win. If they buy once every 3 years, the margin for error is tiny.

- Gross margin: High margins give you room to acquire customers and absorb operational complexity. Low margins force you to be ruthlessly efficient.

- Assortment depth and expansion pressure: The broader you go, the more inventory, content, and operational overhead you create, unless your model changes.

- Dependence on paid acquisition: The more your growth relies on buying traffic, the faster you collide with rising CAC and channel saturation.

- Inventory intensity and lead times: Long lead times and large MOQs (Minimum Order Quantity) turn growth into a cash flow problem, not a demand problem.

- Operational complexity: Returns, split shipments, customer service edge cases, and supplier variability – these scale non-linearly.

So instead of asking, “Are we above X million GMV yet?” a better question is, “Are we starting to pay more for each additional unit of growth than we did last year?”

If the answer is yes, you’re approaching the wall, regardless of the GMV number on your dashboard.

Classic eCommerce model: How growth actually works

In a classic eCommerce setup, growth comes from two main levers: demand and supply.

On the demand side, you grow by acquiring customers. That usually means paid channels, SEO, email, and retention loops. Early on, these compounds. Cheap traffic exists. Audiences are underexposed. Small improvements in conversion create visible lifts in GMV.

As you scale, that dynamic changes. You exhaust the cheapest demand first. Each next cohort costs more to acquire, while conversion gains get harder to find. Growth continues, but the slope flattens.

On the supply side, you grow by expanding assortment. More SKUs mean more chances to match demand. In a classic model, that expansion is funded by your balance sheet. You buy inventory, hold it, forecast demand, and absorb the risk.

This creates the "Inventory Spiral": more SKUs lead to higher forecasting errors, which result in simultaneous overstocks and stockouts. Approximately 42% of small-to-mid-market businesses struggle with overstocking, which ties up cash flow and necessitates heavy discounting to clear obsolete stock.

The financial drain of inventory distortion – the combined loss from missed sales and holding costs – is estimated to account for 11.7% of total revenue for retailers. For a brand at $50 million GMV, this represents nearly $6 million in annual lost value, a "tax" that limits the capital available for marketing or technological innovation.

What matters here is that both levers scale linearly. To grow demand, you spend more. To grow supply, you commit more capital.

There are no built-in loops where growth reduces its own cost. Every additional unit of GMV requires proportional effort, coordination, and risk. When execution is strong, this model can take you far. When scale introduces friction, the cost curve turns.

This is why many teams feel stuck even while GMV is still growing. You’re doing the same things that worked before, just at a higher volume, with thinner margins and less room for error.

Once growth behaves this way, optimization helps at the edges, but it doesn’t change the underlying math. That’s when the limits of classic eCommerce start to show up in practice.

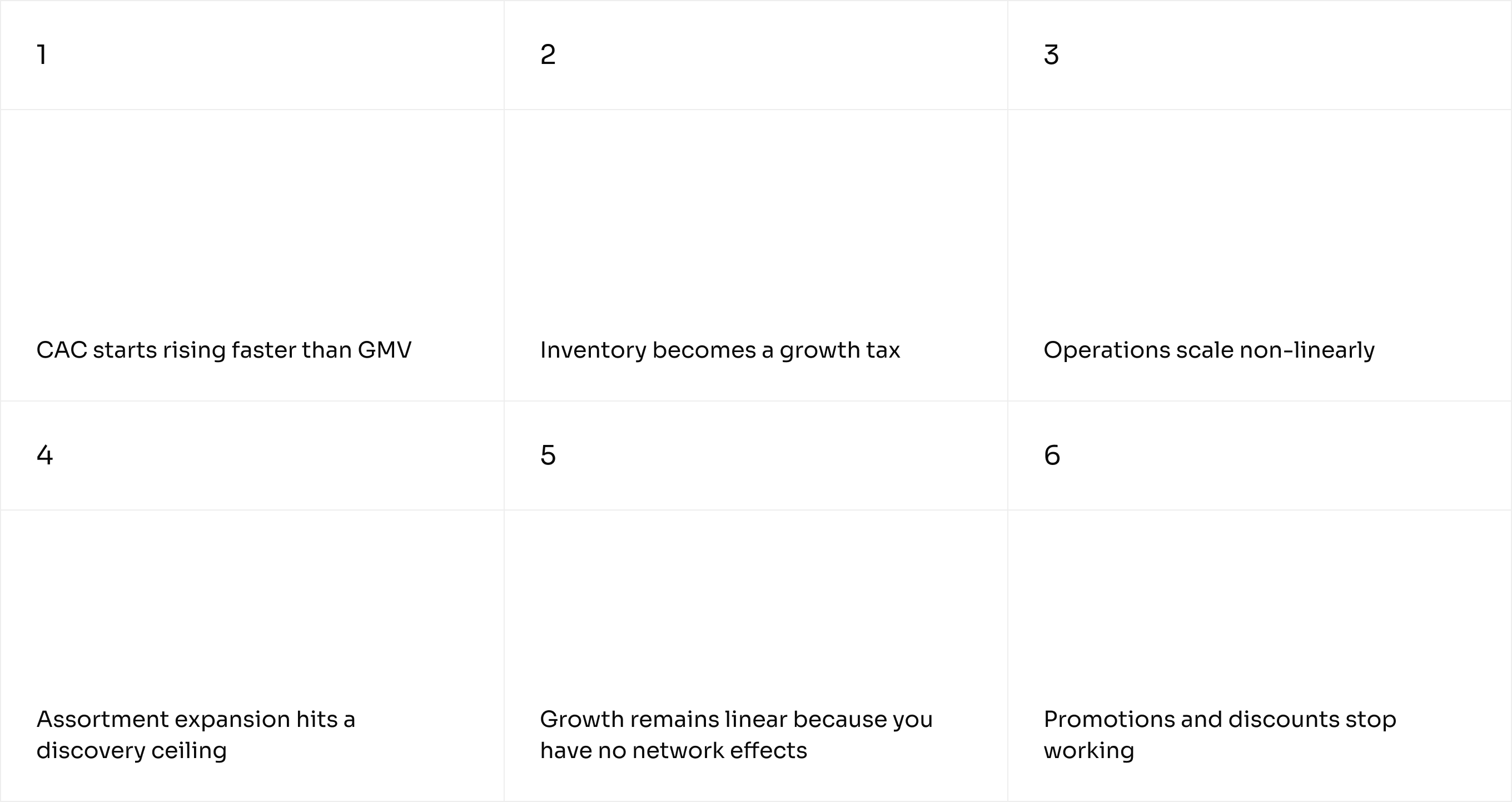

When classic eCommerce starts breaking down: 6 scaling barriers

GMV can keep growing for a long time after the scaling wall appears. What changes first is the quality of that growth. Revenue increases, but profit stops following. Margins flatten, contribution weakens, and more of each quarter’s result depends on discounts, higher acquisition spend, or inventory bets with longer payback periods.

At the same time, operations begin to matter in a different way. Returns, split shipments, customer support edge cases, supplier delays, and fulfillment exceptions take up more attention. Teams spend more time keeping the system stable and less time pushing it forward. Growth is still there, but it starts to feel heavier.

Once growth slows, the symptoms don’t appear all at once. You usually notice them in fragments: one quarter CAC jumps, another quarter cash feels tighter, then operations start absorbing more time than expected. Each issue looks manageable on its own.

The problem is that they rarely come alone. In a classic eCommerce model, scale introduces a set of structural pressures that reinforce each other. Fixing one area often pushes cost or complexity into another. Over time, growth feels heavier, even when GMV is still going up.

If you recognize two or three of the patterns described below, it’s a sign you’re facing a business model problem. The barriers below show up across categories and markets. The order may differ, but the pattern is consistent.

1) CAC starts rising faster than GMV

Early on, growth often comes from underpriced attention: niche audiences, low-competition keywords, cheap retargeting pools, and organic lift. At scale, those channels saturate. You’re forced into more expensive auctions, broader audiences, and lower-intent traffic.

How it shows up:

- ROAS (Return on Ad Spend) declines even when creative and targeting improve.

- You rely more on discounts to keep conversion stable.

- Revenue grows, but contribution margin doesn’t.

What top players do:

- Invest in demand creation, not just demand capture (content, community, partnerships).

- Build retention and repeat purchase loops so LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) can keep up with CAC.

- Expand the value proposition beyond “products” (services, bundles, subscriptions).

2) Inventory becomes a growth tax

To keep GMV growing, you expand the assortment. In a classic model, that often means buying more stock, across more SKUs, with more uncertainty. The result: capital gets locked, forecasting becomes harder, and you start paying for growth with cash flow risk.

How it shows up:

- “We’re growing, but always tight on cash."

- Stockouts and overstocks increase at the same time.

- End-of-season markdowns become a strategy, not an exception.

What top players do:

- Shift selection growth away from owned inventory (dropship, vendor-managed inventory, 3P).

- Use data to enforce assortment discipline (kill SKUs faster, test before scaling buys).

- Negotiate supply terms that reduce risk (consignment, better payment terms, shorter lead times).

3) Operations scale non-linearly

At a small scale, a strong team can “hero” through complexity. At a larger scale, exceptions become the norm: split shipments, delayed suppliers, returns, fraud, missing items, address issues, warranty claims, and customer impatience. The business starts absorbing costs that aren’t visible in the GMV chart.

How it shows up:

- Cost per order doesn’t go down, it creeps up.

- Customer service tickets per order increase.

- NPS declines even though the product is still great.

What top players do:

- Standardize processes and policies early (returns, disputes, SLAs).

- Build tooling that reduces manual handling (automation, clear exception flows).

- Move complexity to where it belongs (e.g., vendors handle fulfillment in 3P models).

4) Assortment expansion hits a discovery ceiling

More products are not automatically more valuable. At some point, “more SKUs” creates confusion, content debt, and a worse shopping experience, unless discovery and merchandising mature accordingly.

How it shows up:

- SEO growth plateaus because content can’t keep up.

- On-site search becomes a constant problem.

- Merchandising becomes subjective (“We need better recommendations”).

What top players do:

- Treat discovery as a product (search, filters, ranking, personalization).

- Use suppliers and vendors as content engines (feeds, enriched data, standards).

- Expand selection without expanding internal content workload proportionally.

5) Growth remains linear because you have no network effects

Classic eCommerce is fundamentally linear: you either buy demand (marketing) or buy supply (inventory). Each incremental step up requires proportional effort. That’s fine until the cost curve turns against you.

How it shows up:

- Every additional +1M GMV costs more than the previous +1M.

- Scaling feels like adding people, tools, and budget – not building leverage.

- Competitors can copy your playbook because it’s the same set of levers.

What top players do:

- Shift from a “store” to a “platform” mindset where others contribute value.

- Build ecosystems: vendors, partners, creators, service providers.

- Create compounding loops (more selection → better conversion → more suppliers → better economics).

6) Promotions and discounts stop working

As acquisition gets more expensive and assortment grows, discounts become a way to compensate for friction elsewhere in the system. They start filling gaps created by high CAC, poor discovery, or inventory pressure.

Over time, customers anchor on the discounted price. Full-price demand weakens. Promotions shift from a tactical tool to a structural dependency. When promotions stop moving the needle, it’s usually a signal that the model itself needs to change, not the offer.

How it shows up:

- You need discounts more often to maintain baseline conversion.

- Promo periods stop outperforming “normal” weeks by a wide margin.

- Margin erosion accelerates faster than volume growth.

What top players do:

- Reduce reliance on blanket discounts and tighten promo scope.

- Shift incentives toward bundles, services, and non-price benefits.

- Focus on improving conversion drivers that don’t compress margin.

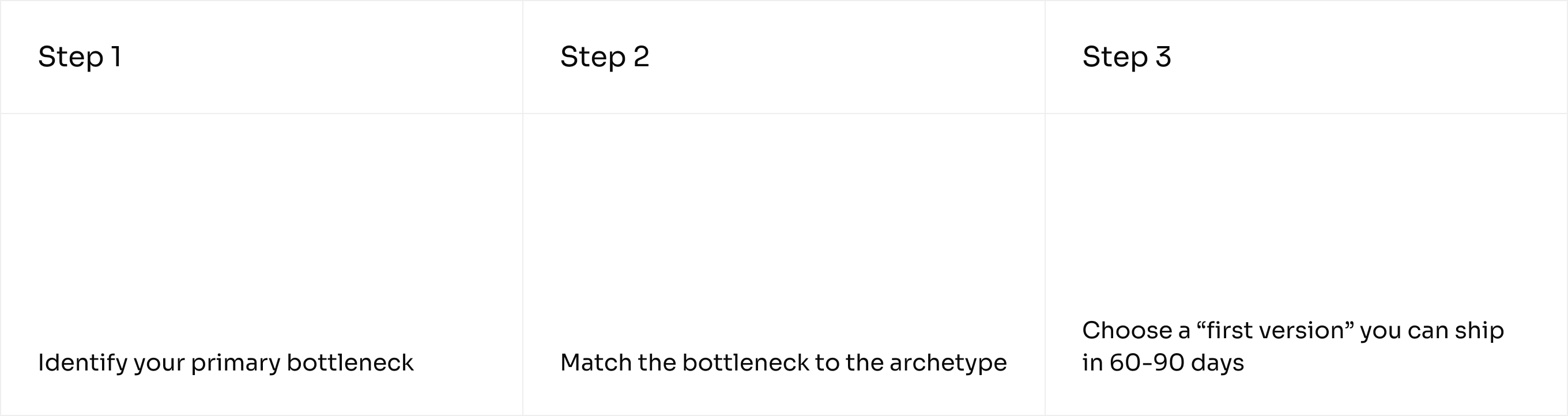

What to change in your business model? Decision framework for CEOs

At this stage, the problem is no longer eCommerce but the growth engine.

Your growth starts getting expensive because the current engine stops producing leverage at scale. The issue sits deeper than campaigns, tooling, or execution. It comes from how demand, supply, and operations are structured in the model.

The main task now is to identify what currently limits your growth. In most scaled eCommerce businesses, the constraint sits in one of five areas: demand, margin, cash flow, operations, or differentiation. One of them usually dominates and shapes the rest of the system.

Use the questions below as a lightweight diagnostic. The goal is to notice a dominant pattern that explains why growth has started to slow and costs more to sustain.

Step 1: Identify your primary bottleneck

If you answer “yes” to most questions in a block, that’s likely your current constraint.

A) Demand is getting expensive.

- Paid channels are saturated, and CAC has climbed for 2+ quarters.

- You need promotions more often to maintain conversion.

- Growth feels like “spend more” rather than “compound more.”

B) Cash flow and inventory are the choke points.

- You’re often tight on cash despite growing GMV.

- You carry a meaningful amount of slow-moving stock.

- Expanding assortment means bigger buys, bigger risk, longer payback.

C) Operations are dragging growth down.

- Support tickets per order are rising.

- Returns, exceptions, and disputes take too much manual work.

- Customer experience is becoming inconsistent across the journey.

D) Differentiation is weakening.

- Competitors can match your selection and price easily.

- You’re increasingly dependent on ad auctions for growth.

- Your brand story is not enough to defend the margin.

Step 2: Match the bottleneck to the archetype

Now, map your bottleneck to the move that most directly changes the cost curve.

- If demand is expensive (A): Prioritize ecosystem/services and partner distribution. Create reasons to choose you that aren’t bought in an ad auction.

- If cash flow/inventory is the choke point (B): Prioritize 3P/dropship/marketplace. Expand selection while shifting inventory risk away from your balance sheet.

- If operations are the drag (C): Prioritize standardization + a narrow 3P model only if you can enforce SLAs. Reduce exceptions, move complexity to structured flows, and avoid “chaos at scale.”

- If differentiation is weak (D): Prioritize services/ecosystem and the B2B layer. Deepen value delivered and increase repeat frequency so you’re not competing on price.

Most businesses end up combining two moves: one to unlock selection or cash flow, and one to build defensibility.

Step 3: Choose a “first version” you can ship in 60-90 days

The fastest way to get it right is to pick an initial scope that produces a measurable signal:

- One category, curated supply, strict rules,

- One service, one partner, one workflow

- One B2B segment, a minimal account experience,

- One partner channel, clear incentives, clear tracking.

A good first version answers one question: “Can we change the economics of growth without breaking the customer experience?”

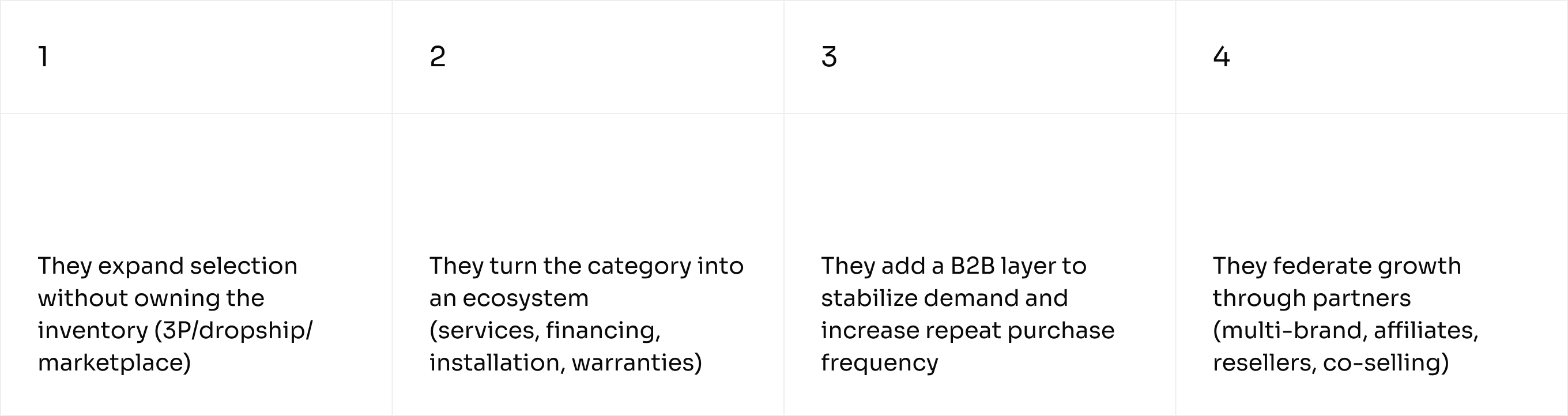

What the best players do with this problem: 4 proven moves beyond classic eCommerce

Once you accept that the scaling wall is structural, you can double down on what already works, fix the bottlenecks that slow growth, or stop an idea before it starts consuming time and capital. The point is to let the growth model evolve along with the business.

Pushing the same engine harder rarely changes the outcome. Scale introduces constraints that can’t be removed with better execution alone. Growth needs to come from a different structure, one that creates leverage instead of adding weight. The organizations that successfully scale past the $50 million ceiling are those that transition from being a "store" to becoming a "platform".

The best players don’t treat this moment as a failure of eCommerce. They treat it as a signal to adjust the model behind it and move into one (or a combination) of these four archetypes.

1) They expand selection without owning the inventory (3P/dropship/marketplace)

Instead of funding assortment growth with their own balance sheet, they let partners carry more of the inventory risk. This unlocks breadth and long-tail coverage without turning cash flow into the bottleneck.

Why it works:

- More selection without proportional working capital.

- Faster category expansion and testing.

- Better availability and lower stock risk.

Where it can fail:

- If you don’t control quality standards, SLAs, and customer experience.

- If vendor operations are inconsistent, you end up absorbing the complexity anyway.

The “first version” (low-risk):

Start with a single category where you already have demand, invite a small set of curated suppliers, and define strict rules for listings, shipping times, and returns. Keep it narrow, and learn fast.

2) They turn the category into an ecosystem (services, financing, installation, warranties)

Top players stop thinking in “products shipped” and start thinking in outcomes delivered. They add complementary services that increase AOV, boost conversion, and create differentiation that competitors can’t copy with a price match.

Why it works:

- Higher gross profit per customer without just raising prices.

- Stronger retention and repeat loops.

- More reasons to choose you beyond product selection.

Where it can fail:

- If services are bolted on without operational ownership.

- If it becomes a margin leak due to refunds, disputes, or poor partner execution.

The “first version” (low-risk):

Pick one service that solves a painful post-purchase problem (e.g., installation, pickup/returns, extended warranty) and build it with one trusted partner before scaling.

3) They add a B2B layer to stabilize demand and increase repeat purchase frequency

Many categories have a natural B2B adjacent market: small businesses, professionals, resellers, and institutions. The best players build a dedicated B2B motion with pricing, invoicing, assortment rules, and account workflows, not just “a discount code for companies.”

Why it works:

- Higher frequency and predictable volume.

- Lower marketing volatility vs consumer-only growth.

- Stronger lifetime value driven by relationships, not ads.

Where it can fail:

- If you treat B2B like B2C with different prices.

- If operational requirements (credit, terms, support) aren’t in place.

The “first version” (low-risk):

Start with your existing customers who buy repeatedly, offer account-based pricing and invoicing, and build minimal workflows for repeat ordering and approval.

4) They federate growth through partners (multi-brand, affiliates, resellers, co-selling)

Instead of relying purely on internal acquisition, top players build distribution leverage. They enable others to sell, refer, or bring supply into the ecosystem - and make that channel structurally attractive.

Why it works:

- Customer acquisition becomes partially “outsourced.”

- Better reach into niches and communities you can’t buy efficiently.

- Compounding referrals and partner loops.

Where it can fail:

- If incentives are unclear or economics don’t work for partners.

- If attribution and payouts create friction.

The “first version” (low-risk):

Choose one partner type (e.g., agencies, consultants, category influencers, or B2B resellers), define a simple offer and tracking, and run a 30-day pilot with 5-10 partners.

The important point is that these moves are structural shifts that change the cost curve of growth. They don’t require a full reset of the business. In practice, the strongest teams extend the one they already have.

That’s why marketplaces usually show up as an addition to existing eCommerce, not a replacement. Core assortment, owned inventory, and direct operations continue to exist. The marketplace layer sits next to them, taking on the parts of growth that no longer scale well inside a classic model.

- Selection can expand without tying up more capital.

- New categories can be tested without large inventory bets.

- Growth can involve suppliers and partners, not just internal teams.

Most teams don’t commit to this all at once. They start narrow, prove the economics, and layer additional archetypes only after the first one works. The result is an evolved model, not a replatforming project.

To understand how this shift can improve your growth, look at how marketplaces and classic eCommerce differ at the model level. See why that difference shows up directly in the cost curve of growth.

Marketplace vs eCommerce platform comparison: How the business model changes the cost curve

Once growth stops compounding inside a classic eCommerce setup, improving the cost curve requires more than optimization. It requires a model that creates leverage as scale increases.

Marketplace models change how growth is funded, how risk is distributed, and how effort translates into GMV. That’s why they often appear as the next step once classic eCommerce reaches its limits.

Why an eCommerce platform is optimized for owned inventory

Most eCommerce platforms are designed around a single merchant owning the transaction. Pricing, fulfillment, returns, tax logic, and customer support assume centralized control.

This works well for classic eCommerce, but it limits how far the model can stretch. Adding vendors on top of this structure often means manual work, edge cases, and operational friction.

What a marketplace platform needs to handle instead

A marketplace is built around coordination rather than ownership. It needs to handle multiple sellers, separate payouts, different fulfillment paths, shared customer experience rules, and enforcement of standards.

The focus shifts from executing every step internally to orchestrating how others participate in the system while keeping quality and trust consistent.

Why “adding vendors” is not the same as running a marketplace

Adding vendors to an eCommerce setup often looks simple at first. Products appear. Orders come in.

The complexity shows up later: split carts, partial shipments, disputes, returns, SLAs, payouts, and accountability when something goes wrong. Without a model designed for this, the platform absorbs the cost instead of reducing it.

A real marketplace works because the model, not the team, carries that complexity. Rules, incentives, and workflows replace manual coordination. That’s what allows growth to scale without turning into operational drag.

Ecommerce vs marketplace economics

The fundamental economic difference between classic eCommerce and a marketplace is the shift from capturing the full product margin to earning a "take rate" or commission on 3P sales.

While the per-unit revenue is lower in a commission model, the operational cost and financial risk are drastically reduced. Typical marketplace commission rates range from 10% to 30%, depending on the category and level of service provided by the platform.

In classic eCommerce, growth is funded internally. You acquire demand, buy inventory, hold risk, and capture margin. Every increase in GMV depends on your ability to spend more on acquisition and commit more capital to stock.

In an online marketplace model, part of that burden shifts outward. Suppliers fund inventory. Marketplace sellers expand selection. GMV grows through participation, not just internal investment. The economics change because growth no longer depends entirely on your balance sheet.

Inventory risk vs supply aggregation

Classic eCommerce grows by owning more inventory. That works until assortment depth and forecasting error start locking up cash and slowing decisions.

Marketplace models grow by aggregating supply. Inventory risk sits with suppliers, not the platform. This allows selection to expand without proportional increases in working capital, and it lowers the cost of testing new categories or long-tail demand.

Linear growth vs compounding loops

In a store model, growth is linear. More GMV requires more spending, more inventory, and more operational capacity. Each step up costs at least as much as the previous one.

The marketplace model introduces compounding loops. More supply improves selection. Better selection improves conversion. Higher conversion attracts more suppliers. Growth starts reinforcing itself instead of adding weight at each step.

How to add a marketplace to your existing eCommerce?

Adding a marketplace layer is often discussed as a big platform change. In practice, most teams struggle not because the idea is wrong, but because the execution path is unclear.

Without a structured way to add a marketplace layer:

- growth experiments become expensive and slow,

- Inventory risk concentrates further inside the business,

- Operational complexity increases instead of moving outward.

In many cases, “adding vendors” ends up increasing internal workload instead of reducing it. The cost curve gets worse, not better. One of the biggest risks in marketplace projects is unclear ownership of logic. A successful integration starts with a clean separation of responsibilities.

The transition to a marketplace requires a technological architecture that can handle multi-vendor logic without destabilizing the core commerce engine. Attempting to "bolt-on" marketplace features to a standard eCommerce monolith often leads to failure. Instead, modern architectures utilize a decoupled, API-first approach.

The most effective approach is to extend your existing eCommerce model with a marketplace layer that is designed for coordination. For businesses already operating on established platforms like Magento (Adobe Commerce) or Shopify, the scaling wall often appears as a performance or maintenance ceiling.

The Mercur framework allows these organizations to extend their existing storefront into a multi-vendor platform without a "big-bang" replatforming. Mercur is a multi-vendor marketplace platform that can be integrated with any eCommerce, ERP-driven, or custom-built platform – adding multiple vendor workflows and marketplace functionality, while your core commerce engine stays untouched.

This separation of concerns ensures that the marketplace logic is isolated and extensible, allowing for the independent scaling of vendors and workflows without slowing down the core performance.

- No migration, no replatforming, no vendor lock-in.

- No need to pause current eCommerce development.

- Works with custom and legacy platforms.

- Clear separation between commerce and marketplace logic.

- API-first, event-driven integration.

This allows teams to:

- Add marketplace sellers without breaking existing flows,

- Keep total control over customer experience rules,

- Avoid long migration projects and platform lock-in,

- Start narrow and expand only after the economics work.

The focus is not on launching a full marketplace on day one. It’s about introducing a structural change to the growth model without disrupting the business you already run.

Before building anything, it’s worth validating how a multi-vendor marketplace should live in your ecosystem. A short architecture conversation can save months of development and years of technical debt. Book a marketplace consultation!

Summary: The scaling wall is a model problem, and that’s good news.

When classic eCommerce stops scaling after X million in GMV, it rarely points to weak execution. Most teams reach this stage by doing many things right. What shows up instead are structural limits built into the model:

- CAC rises as cheap demand saturates.

- Inventory turns into a growth tax.

- Operations become nonlinear and harder to control.

- Assortment expansion hits discovery and content ceilings.

- Growth stays linear because there are no compounding loops.

At that point, optimization still matters, but it stops changing the cost curve. Better campaigns, better tools, and tighter processes improve outcomes at the edges, not the structure underneath.

The companies that move through this phase successfully don’t abandon eCommerce. They evolve the growth engine behind it.

- They reduce their dependence on owned inventory.

- They let partners, suppliers, or services carry part of the growth load.

- They add layers that create compounding effects instead of linear effort.

Often, this happens through a marketplace layer added to an existing eCommerce business – not as a replatforming project, but as an extension of the model.

If there’s one takeaway from this article, it’s this:

The next phase of growth doesn’t come from pushing the same engine harder. It comes from changing how growth is generated in the first place.

If you’re considering the marketplace as your growth engine shift, we can help you define a safe MVP scope for your category – what to build first, what to postpone, and which guardrails to set so you don’t damage the core business. Talk to a marketplace expert!

FAQ on eCommerce platform vs marketplace

What is the difference between a marketplace and eCommerce?

The main differences between eCommerce vs marketplace come down to the business model, control, and how sales scale.

In a classic eCommerce setup, you run your own website and sell products directly to consumers. You manage inventory, prices, quality, and the entire supply chain. This model gives you total control, but growth depends on your ability to acquire new customers, fund inventory, and manage operations across online sales channels.

A marketplace, on the other hand, connects buyers and sellers on one platform. Products come from marketplace sellers or third parties, not from the platform itself. The marketplace focuses on access, discovery, transactions, and rules, while sellers handle inventory and fulfillment. In practice:

- eCommerce scales through owned inventory and direct sales.

- Online marketplaces scale by aggregating supply from many sellers.

- Marketplaces trade total control for reach, brand exposure, and access to more customers.

That’s why many companies move toward a hybrid model, combining an ecommerce platform with a marketplace layer.

What is a marketplace in eCommerce?

A marketplace in eCommerce is a platform where multiple merchants or retailers sell products through a shared shopping experience.

Instead of one company selling from its own inventory, the marketplace allows new sellers, small businesses, or established retailers to list products across different product categories. Buyers can compare prices, quality, and delivery options from multiple sellers in one place.

Common marketplace models include:

- business to consumer (B2C),

- consumer to consumer (C2C), such as vintage items or craft supplies,

- business-focused marketplaces serving multiple markets.

This model works well for expanding into other markets, testing new categories, and reaching potential customers without owning all the inventory.

What is an online marketplace?

An online marketplace is a digital platform that enables transactions between buyers and sellers across one or many markets.

Global marketplaces often operate across regions such as East Asia, Latin America, or Greater China, supporting cross-border selling and access to new markets. Well-known examples include Amazon, eBay, Mercado Libre, and platforms within the Alibaba Group ecosystem.

Compared to online stores, online marketplaces:

- Attract more customers through shared demand,

- Enable sellers to reach global ecommerce audiences faster,

- Lower time constraints for entering new markets.

They are commonly used by small businesses and companies looking to sell online without building traffic from scratch.

Can you use both an eCommerce platform and a marketplace?

Yes, many companies use both the marketplace and their own ecommerce platform at the same time. In this setup:

- The eCommerce focuses on brand control, margins, and direct relationships.

- Marketplaces act as sales channels for customer acquisition and brand exposure.

This approach helps reach new customers, test other markets, and drive revenue without relying on a single channel. It’s especially common for businesses expanding into global marketplaces or multiple markets.

Is a marketplace better than eCommerce for selling products?

The right choice depends on your focus, resources, and growth goals.

Marketplaces are often better for:

- reaching more customers quickly,

- expanding into new markets,

- Selling across multiple product categories.

Ecommerce platforms are better for:

- maintaining total control over pricing and quality,

- managing a custom production process,

- building a direct relationship with consumers.

Many businesses start with eCommerce, then add a marketplace layer once inventory pressure, competition, or scaling limits appear.